|

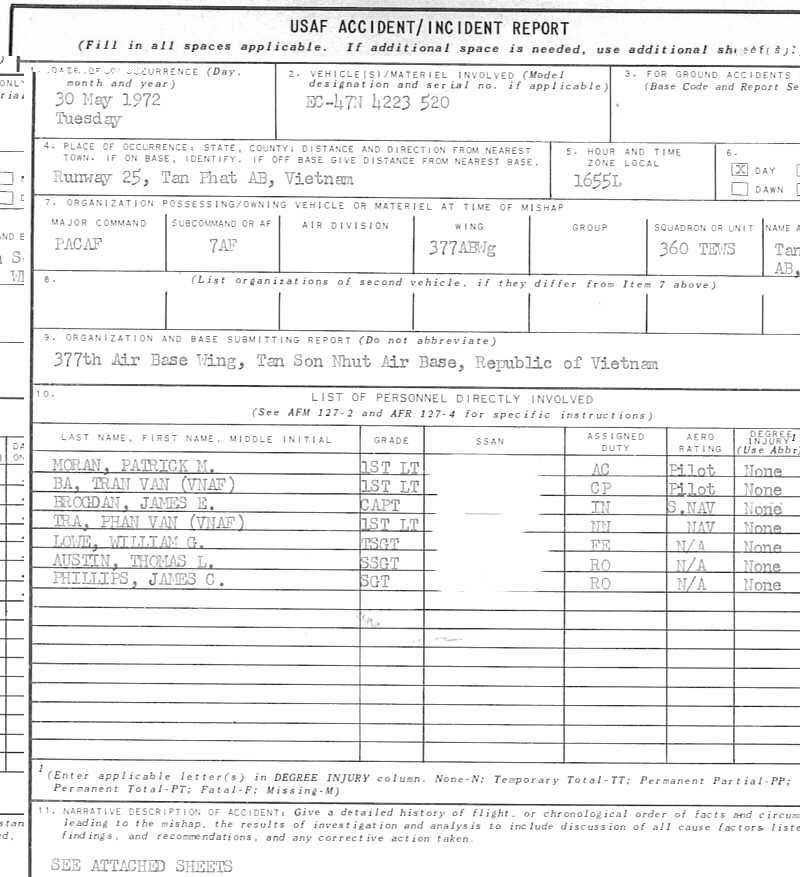

On 30 May 1972, and EC-47N, Serial Number 42-23520, assigned to the 360th Tactical Electronics Warfare Squadron (TEWS), 377th Air Base Wing, Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Republic of Vietnam, was scheduled for a classified tactical mission. Departure from Tan Son Nhut Air Base was scheduled at 1220 Local (All times will be local hereafter) for a mission duration of seven hours. The Aircraft was fueled with 716 gallons of aviation gasoline, and computed takeoff weight was 25,546 pounds. The aircraft’s tactical call sign was LEGMAN 51. First Lieutenant Patrick M. Moran, the aircraft commander of LEGMAN 51 arrived at the Squadron’s briefing room with his crew at 1040 hours. The pre-mission briefing, attended by all crewmembers, included weather, intelligence, airfield data, mission specifics, tactical frequencies and the latest Flight Crew Information File (FCIF) item. Weather for departure time was forcast to be 1100’ scattered, 2300’ scattered, 11,000’ broken, visibility 7 miles, temperature 30 degrees Centigrade, altimeter setting 29.82 Hg, with Cumulo Nimbus to the southwest. All crewmembers reviewed the FCIF, picked up their personal equipment and proceeded to their assigned aircraft. Crew composition for the mission was aircraft commander (hereafter also referred to as the pilot), co-pilot, instructor navigator, student navigator, flight mechanic and two radio operators. Both the copilot and the student navigator were Vietnamese nationals, assigned to the Vietnamese Air Force 5th Air Division and attached for flying to the 360th TEWS. The co-pilot, though occupying the right seat, was a qualified aircraft commander in the EC-47. The crew had not flown together integrally prior to this flight. Arrival at the aircraft was approximately one hour prior to the scheduled takeoff. The crew conducted a thorough pre-flight of the aircraft, had started engines, and was ready to perform the engine run-up when it was notified by the Tactical Unit Operations Center (TUOC), LEGMAN Control, that the mission had been placed on a weather hold. The TUOC had received a severe weather advisory for thunderstorms effective 1300-2100 for the Tan Son Nhut Air Base and vicinity. The crew shut down the engines to await a decision on their launch. Squadron supervisory personnel visited the weather station to analyze the weather situation. They also received a report from another squadron aircraft, LEGMAN 39, inbound from the area to which LEGMAN 51 was to perform it’s mission, that the area and enroute weather was almost clear with haze, scattered clouds, and a few avoidable cumulus buildups. The decision was made and LEGMAN 51 was directed to restart engine, fly the scheduled mission, and, additionally, to make frequent Pilot Reports (PIREPS) enroute to his assigned area. LEGMAN 51 restarted engines, completed all prescribed pre-takeoff checks, and took off at 1240. Shortly after becoming airborne, LEGMAN 51 made a PIREP to the squadron, advising that there was a layer of scattered clouds in the vicinity of Tan Son Nhut Air Base at 2000’. While enroute to the aircraft’s working area, the pilot made two further PIREPs, but indicated to the squadron his ability to safely proceed to the area. The aircraft arrived at it’s assigned area at approximately 1440-1445 hours, but found the area unworkable due to cumulo nimbus buildups and radio interference. This decision was reached at about 1500 hours, and the aircraft was placed on a heading toward Tan Son Nhut at 9500’, an altitude that would keep it in visual flight conditions. While on this course the crew was in frequent contact with other aircraft and was receiving radar advisories from tactical controlling agencies. At 1525 the pilot heard a weather recall for all LEGMAN aircraft. He verified this with another aircraft in his area. The aircraft proceeded in a generally Southwesterly direction toward Tan Son Nhut. After approximately 40 minutes, progress through the buildups became more difficult. The pilot navigated through one line of storms, and then was confronted with another unpenetrable line of cumulus buildups. At this time the pilot elected to reverse course to the Northeast in an attempt to reach either Nha Trang or Cam Ranh Bay Air Bases where a refueling was planned with an eventual return to Tan Son Nhut once weather permitted. Another aircraft was estimated to be 60-70 miles Northeast of Tan Son Nhut Air Base at an estimated time of 1610-1615. After reversing course, the pilot again encountered what he considered to be an unpenetrable line of cumulo nimbus buildups. At this time the aircraft was in a relatively clear area close to the plantation town of BAO LOC which lies Northeast of Tan Son Nhut Air Base at approximately 80 nautical miles. Staying within this clear area, the pilot climbed to 13000 feet and then descended to 4000 feet in an attempt to find a way through the weather which had by now deteriorated to solid lines of thunderstorms in all directions. During this period the crew observed two airfields within this clear area. After consulting the navigator and co-pilot on the possibility of penetrating through the weather and on the identification and suitability of the observed airfields, the pilot elected to land at one of the airfields and wait for the weather to improve. The selected airfield was TAN PHAT (VA2-301) but was misidentified as BOA LOC Plantation (VA2-37). The obvious discrepancies in runway heading, length, composition, etc., were explained by the co-pilot (who has relatives living in the area and is familiar with this area), as being due to resurfacing and improving the airfield. The pilot accepted this explanation and prepared for a landing. The Approach and Landing Date portion of the Descent Checklist was accomplished. The pilot circled the airfield several times and made on low approach, estimated a##not lower then 500’ above the ground. The windsock was observed and the pilot turned on to a right downwind for a landing on runway 25. The Before Landing Checklist was accomplished and the aircraft turned onto final approach. Full flaps were lowered in preparation for a short field landing. The approach was normal at 85-90 kts and the aircraft landed an estimated 300-400 feet from the approach and at 16## hrs. The aircraft bounced slightly and settled back to the runway. At this time the pilot saw a motorcycle with two people on it start to cross the runway from right to left immediately in front of the aircraft. The pilot applied power and jerked the control column back, in a successful attempt to avoid hitting the motorcycle. The aircraft started to stall (estimated 25-40 feet attitude {altitude maybe} and the left wing started to drop. The aircraft touched down firmly, left gear first, on the left side of the centerline, heading left of the runway heading. Full right rudder, and then right brake was used in an attempt to align the aircraft with the runway. The aircraft was still heading toward the left edge of the runway and the pilot elected to use heavy braking in an attempt to stay on the runway and/or stop the aircraft as soon as possible. The aircraft tipped forward and both propellers contacted the runway. During the subsequent maneuvering the propeller housings, heavily damaged by the ground contact, failed completely allowing the propellers for fall off the engines. The left propeller went under the aircraft, tearing holes in the right auxillary fuel stress panel, the fuselage just aft of the wing root and the right horizontal stabilizer. At the time of the heavy braking the aircraft was almost parallel to the runway. The left main gear went a maximum of two feet off the paved surface for a distance of 175-200 feet. The aircraft then started back toward the centerline was straightened out and stopped approximately 2100 feet from the approach end, four feet to the right of the centerline. After the aircraft was stopped engine shutdown was completed and the crew evacuated the aircraft. No one was injured during the landing sequence or egress from the aircraft. After determining there was no danger of fire the aircraft was re-entered and radio contact was established with Military Airlift Command aircraft overflying the area. The message was relayed to the 360th TEWS that LEGMAN 51 was at BOA LOC after a forced landing. Contact was also made through ARVN personnel to US Army Advisors who assisted the crew in clearing the aircraft from the runway and in arranging for assistance in the security of the aircraft.

|

|

MISSION: On 30 May 1972, an EC-47N, Serial Number 42-23510, assigned to the 360th Tactical Electronics Warfare Squadron, (TEWS), 377th Air Base Wing (PACAF), Tan Son Nhut Air Base, RVN, was scheduled to conduct a classified mission with a scheduled takeoff of 1220 local. Tactical call sign for this mission was LEGMAN 51. The flight crew, assigned to the 360th TEWS or as otherwise noted, consisted of an aircraft commander, 1st Lt. Patrick M. Moran; copilot, 1st Lt. TRAN VAN BA, assigned by the Vietnamese Air Forces 5th Air Division to the 360th TEWS for training; Instructor navigator, Captain James E. Brogdon; Student navigator 1st Lt. PAN VAN TRA, assigned to the 36oth TEWS for training; Flight mechanic, TSgt William G. Lowe; and two radio operators, SSgt Thomas L. Austin and Sgt James C. Phillips, of the 6994th Security Squadron attached for flying to the 360th TEWS. The aircrew had not flown together previously, the integral crew concept being an unworkable one for the 360th TEWS because of frequent personnel changes in the unit. The aircraft in which the crew was to conduct it’s mission was fueled with 716 gallons of aviation gasoline with the projected takeoff gross weight of 25,546 well below the maximum of 29,000 lbs as contained in PACAF Manual 55-47. Fuel was adequate for the planned mission. The mission was scheduled for seven hours duration, with the actual location and mission to be flow classified. The investigating board found nothing in the scheduled mission, crew composition, or aircraft configuration that in any way could have been a causative factor in this accident. PREFLIGHT PREPARATION: The entire flight crew reported to 360th TEWS Operations for it’s pre-mission briefing at 1040 hours. Discussions with Squadron Supervisory personnel revealed that it is unit procedure to schedule the pre-mission briefing between one hour and thirty minutes and two hours prior to takeoff to accommodate more than one crew. The briefing was a comprehensive one including time hack, takeoff times, current airfield data, weather forecasts for Tan Son Nhut and several other bases, radio frequencies, strike notification, flying safety and the latest Flight Crew Information (FCIF). All mission planning was adequate. After the briefing, which lasted some 15-20 minutes, the flight crew individually rechecked their FCIF cards and proceeded to the Squadrons life support section where they secured all necessary items of personal equipment for the flight. The crew arrived at their aircraft approximately one hour before scheduled takeoff time and all preflight actions were completed in accordance with technical order procedures. The aircraft’s engines were then started and at approximately 1215 the crew was informed by it’s Tactical Unit Operations Center (TUOC) call sign, LEGMAN CONTROL, that a severe weather advisory, valid from 1300 to 2100 hours, for thunderstorms in the Tan Son Nhut area had been received. The crew was advised to shutdown engines and the mission was placed on a weather hold. Squadron Supervisory personnel personally visited the Vietnamese Air Force weather station and analyzed the radar presentation. Concurrently, another unit aircraft, LEGMAN 39, reported that it was inbound to Tan Son Nhut from the area in which LEGMAN 51 was to perform it’s mission. LEGMAN 39 reported no difficulty either in performing it’s mission or in maintaining visual flight. Squadron Supervisory personnel, after analyzing the radar depictions and the pilot report (PIREP) from LEGMAN 39, made the decision to launch LEGMAN 51. LEGMAN 51 was advised to restart engines and proceed with it’s scheduled mission. LEGMAN 51 was requested to furnish additional PIREPs when airborne. Starting, pre taxi, taxi run up, before takeoff and lineup checklists were performed routinely and the aircraft took-off, reporting to LEGMAN CONTROL shortly thereafter a takeoff time of 1240. The board analyzed all crew preflight preparations and concluded that these were complete and performed properly. FLIGHT: The flight of LEGMAN 51 from it’s takeoff to the time it arrived in it’s assigned mission area was uneventful. At the altitude and on the course chosen, the pilot was able to maintain visual conditions without difficulty. The pilot reported enroute isolated thunderstorms in his statement, but nothing of such severity as to preclude his arriving at his briefed location. He made three PIREP’s enroute, none of which gave any indication that weather was a problem. Arriving at their briefed mission area at 1445, the crew attempted to perform their mission, but found that the area was unworkable due to thunderstorms and electrical interference. At 1500, the pilot made a decision to proceed toward Tan Son Nhut in order to receive alternate mission instructions from his TUCC. The pilot turned his aircraft southwesterly and at an altitude of 9500’ proceeded toward Tan Son Nhut. At 1525 a message was received that all LEGMAN aircraft were to return to Tan Son Nhut. Up to this point, none of the statements, testimony or interviews indicated any problems encountered by the pilot or crew in circumnavigating the thunderstorms. The pilot was using visual sighting and his onboard radar with interpretive assistance by the navigator as well as radar advisorys by Paris Control, a tactical controlling agency located at Tan Son Nhut Air Base. During the investigation, Paris Control advised that taped conversation between Paris and LEGMAN 51 were unusable, but aircrew statements indicate that this exterior assistance was used. The aircraft continued toward Tan Son Nhut, but the crew faced increasing difficulty in circumnavigating the thunderstorms, which between 1525 and about 1605 had become more numerous, more intensified and began to form in definite lines. Heading was altered numerous times and one of these thunderstorm lines was successfully negotiated by the pilot with assistance of the navigator using the onboard radar. Soon thereafter the aircraft came upon another line of storms and the crew was unable to locate a safe path through this line. The pilot at this point, made a decision to reverse course and attempt to reach a suitable alternate field where refueling was to be accomplished before further attempts to reach Tan Son Nhut were made. His position at this time was 60-70 miles from Tan Son Nhut. After reversing course and circumnavigating cumulus buildups, the aircraft was in a relatively clear area; but the pilot found that he was in a sense, becoming boxed in by surrounding storms, effectively eliminating, in his mind, further penetration or circumnavigation at that altitude. The pilot then initiated a climb to 13,000’ , using oxygen, in an attempt to fly over the weather, but once more found no way through. At this time he was in a relatively clear area at approximately 80-90 miles northeast of Tan Son Nhut. He decided to descend in an attempt to fly under the weather to an alternate base; an during his decent noticed two small airfields in the clear area below. While keeping the fields in sight; the pilot continued his descent to approximately 4500’ MSL, still looking for a way to an alternate on the Vietnamese coast. Both Nha Trang and Cam Rahn Bay Air Bases were suitable weather alternates at the time. Again, due to low clouds, heavy precipitation and the high terrain known to be in the area, no safe way could be found through or around the storms. It was at this point, at approximately 1640 that the pilot made his decision to land at one of the fields sighted, rather that to continue with what had been several futile attempts to circumnavigate severe weather. The pilot consulted the navigator and copilot on the identification of the airfields. There were only two airfields in the immediate area shown on the charts used by the navigator, BAO LOC (VA2-260) and BAO LOC Plantation (VA2-37). The selected airfield TAN PHAT (VA2-301 was the most satisfactory airfield available but was misidentified as BOA LOC Plantation (TAB R). When the pilot noted the obvious discrepancies between the depiction of BOA LOC Plantation in the Tactical Aerodrome Directory (TAD) and the selected airfield, the copilot explained that he had relatives living in the area, was familiar with the area, and that the BOC LOC Plantation runway had recently been lengthened and the runway reoriented. The pilot accepted this explanation and did not positively identify the airfield at which he was landing. Charts (DOD-Flight Information Publication – Special Southeast Asia Tactical VFR Chart) were on board the aircraft and do show TAN PHAT airfield. The decision and factors involved in this decision to land were examined. First Air Weather Service, the Board members acknowledged that thunderstorms had been forecast for the entire area and that the pilot was aware of the forecast prior to departure. Although the localized concentration of storms was heavier than anticipated, the pilot had ample warning of their existence; therefore Air Weather Service is not considered a causative factor. Weather factor was reviewed. It is a definite fact that the adverse weather was the factor that made the pilot decide to land. However the selected airfield was in fact VFR. The plot was able to establish a satisfactory approach and had other factors not appeared the landing would have been accomplished safely. Therefore weather, although a factor in the decision to land, was not a causative factor in the accident. The pilots decision to land: Faced with what appeared to be complete encirclement by thunderstorms and having located an airfield that was VFR and identified (although falsely) as a suitable secure airfield, the Board could find no fault with the pilots decision to land. Misidentification of the airfield: The Board acknowledge that the pilot was given poor assistance and misleading information by other crew-members in the identification of the airfield. Had one of the navigators or pilots checked other available charts the field would most probably have been correctively identified. Had anyone read the remarks in the TAD under BAO LOC “Traffic Pattern- Caution: TFC PTN CONFLICTS WITH TAN PHAT 1 ¼ MME.” (TABR). The error would probably been corrected. Had the co-pilot not misled the pilot with his (false) knowledge of the BAO LOC Plantation airfield being improved, the pilot would probably have checked further to properly identify the airfield. However it remains the pilots responsibility to properly identify the place of landing, no matter how misleading the information given him may be. Had the airfield been properly identified and the TAD consulted, the pilot would have been aware of the notation for TAN PHAT, “pedestrians and vehicles have free access to RWY “ (TABR). This notation does not appear for either BAO LOC or BAO LOC Plantation. Had the pilot read that notation he may have made a better effort to warn personnel around TAN PHAT that he was in fact going to land. The Board could not say that this would have prevented the motorcycle from crossing, only that it might have. The Board therefore concluded that a possible contributing cause was the pilots failure to properly identify the airfield. Having made his decision to land, the pilot circled the selected field several times and made one low approach of the runway at what he estimated to be no lower than 500’ above the surface. Normal checklist procedures were used and the aircraft was maneuvered to a right downwind leg for TAN PHAT’s runway 25 (See Tab R) which was the most favorable considering observed wind direction. Weather phenomena existing at TAN PHAT can at best be only estimated, the accurate data was not available to the pilot. The pilot stated during a post accident interview that visibility was good with only scattered clouds in the vicinity of the airfield. He stated that he remembered light reain during his descent and that he assumed that the runway would be wet. He judged that the surface wind was at 10 knots, no more than 20 degrees off runway heading left to right. He also was firmly convinced that he was landing on considerably less runway than was actually available, for when reviewing landing and approach data from the copilot he was brief on a runway of 3000’ long by 60’ wide. The Before Landing Checklist was properly completed and the aircraft was placed on a final approach with gear down and wing flaps set at full. Final approach airspeed was 90 knots, judged a bit high but well within operating limits. His estimated landing weight was places during the post accident investigation at close to 23,700 lbs, based on fuel consumed since takeoff. Given a head wind component of 10 knots with flaps full down, temperature 29 degrees centigrade (estimated), density altitude of 5000’, the following data was calculated from T.O. 1C-47-1-1 as optimums for this landing.

Final Approach Speed------------------------------70.0 kts (1.3Vs 130% power off stall) Threshold Speed-----------------------------------65.5 kts (1.2Vs) Touchdown Speed----------------------------------60.0 kts (1.1Vs) Power Off Stall--------------------------------------54.5 kts Landing distance dry runway----------------------1600 ft. Landing distance wet runway (RCR 12)------------2500 ft.

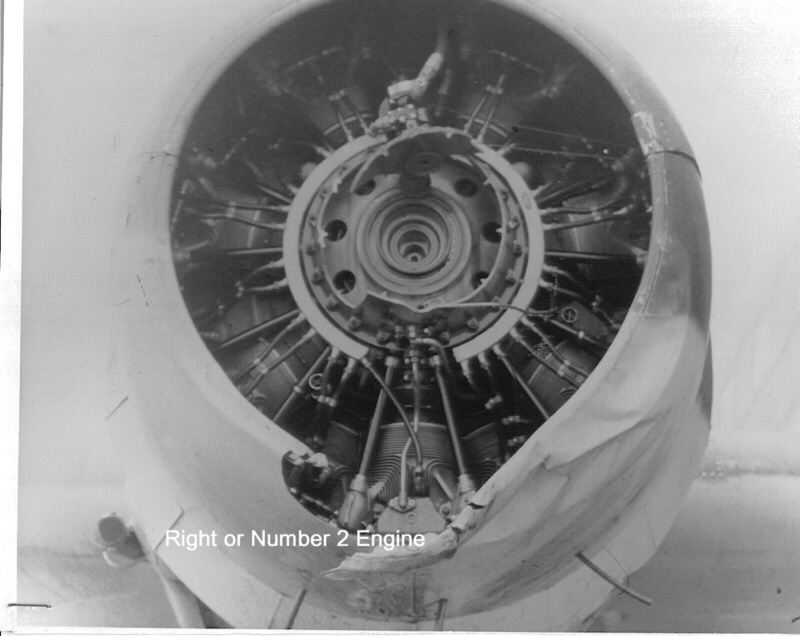

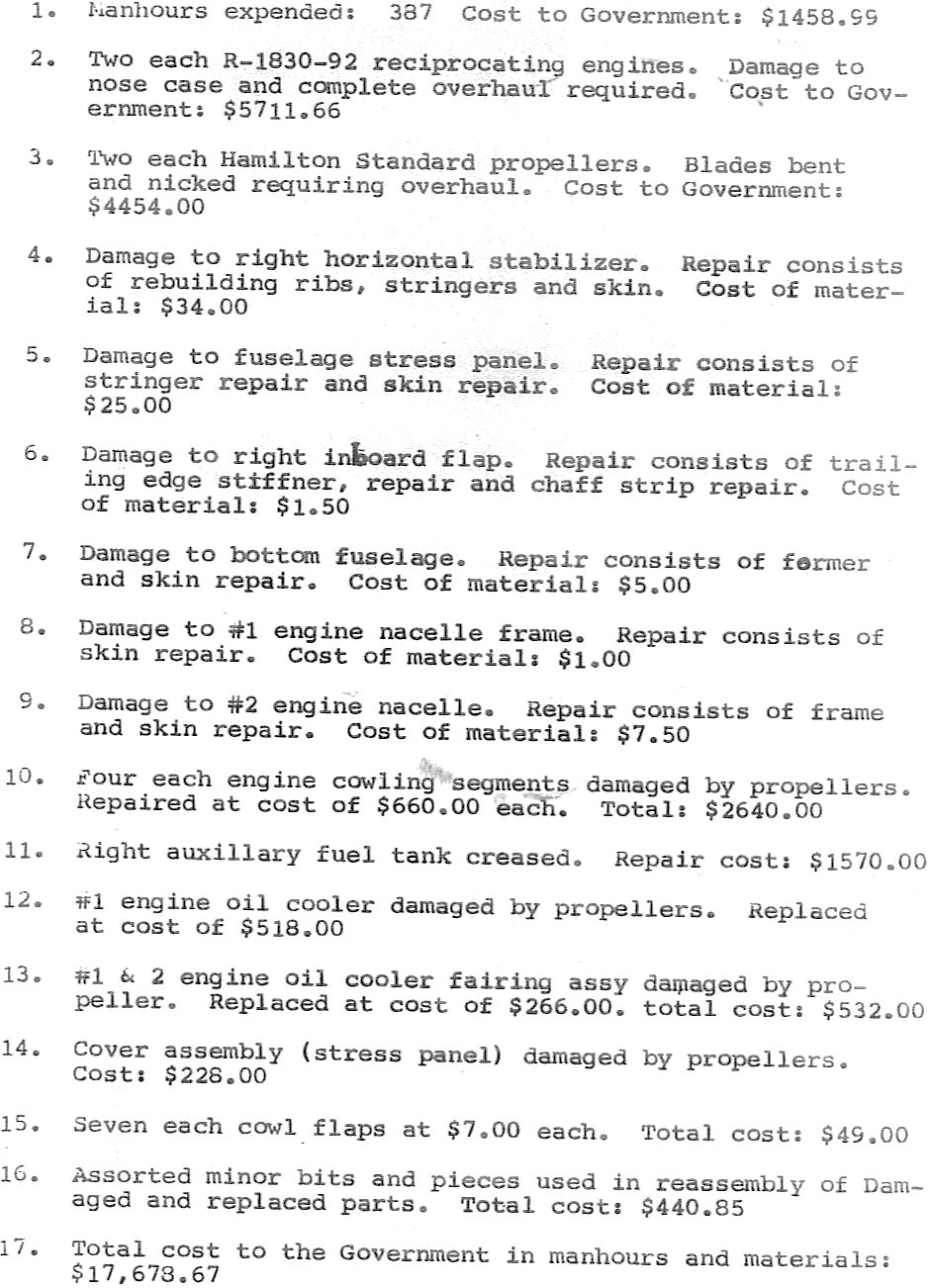

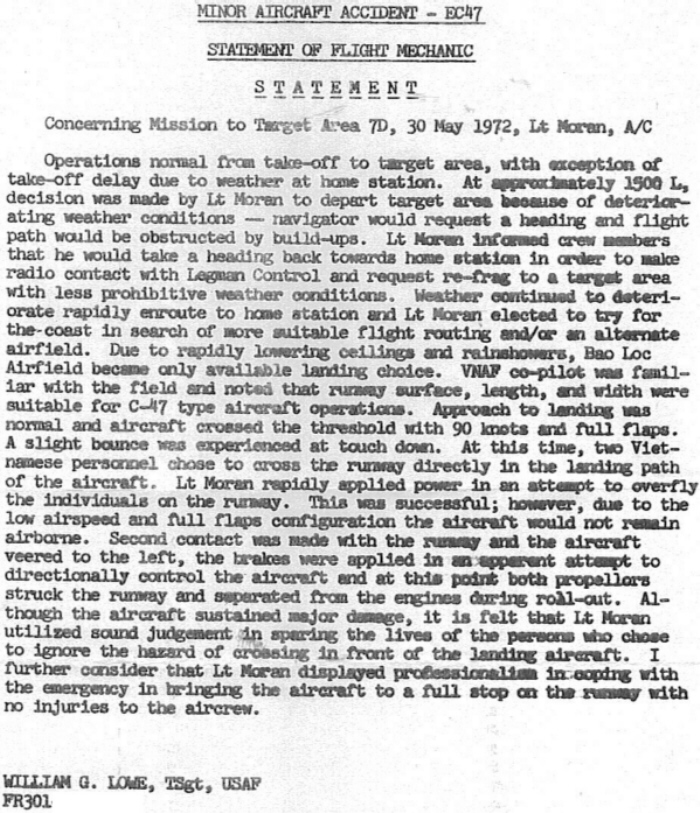

The aircraft, according to crew accounts, made it’s initial touchdown on the centerline with power off between 300-400’ from the runway threshold, bouncing slightly before resettling to the runway. The Board was of the opinion that the landing roll, had nothing occurred, would have been uneventful with the aircraft coming to a safe stop with normal braking on the remaining runway. However, after the initial bounce and subsequent touchdown the pilot observed a motor bike with driver and passenger attempting to cross the runway from the right immediately in front of the aircraft, the point of crossing was determined to be 832 feet from the approach end of the runway on a frequently used crossing (Photo #1, TAB Z). ARVN personnel at TAN PHAT were queried concerning witnesses to the mishap and identification of the driver of the motorcycle. Although several stated they knew someone who had seen the motorcycle cross, not of the actual witnesses could be located. The motorcycle driver apparently left the area without stopping, and no one would admit to any knowledge of who he was. The motorcycle crossing the runway confronted the pilot with a choice of either continuing the landing roll and hitting the motorcycle, with almost certain death to its occupants, or pulling the aircraft off the ground in an attempt to leap over it. He took the latter course of action, applying power, the exact amount undetermined, and pulled the control column aft. This action cleared the vehicle and it’s occupants, but it likewise put the aircraft in a nose high attitude and, according to the pilot’s description of sluggish control forces, close to the point of a stall. Power was still applied to the engines, and the pilot stated that the left wing began to drop. Flight characteristics of the C-47 are such that this is an almost perfect description of an imminent power on stall in which wing rolling occurs. The pilot, recognizing the conditions, retarded the throttles to idle and neutralized the elevator controls, causing the aircraft to drop to the runway, nose down, in a left wing low attitude. The touchdown was described as a hard one by all crewmembers, and from this the Board concluded that the aircraft had gone from a left wing low power on stall immediately to a power off stall, a condition created when power was pulled off with the resultant lowered air flow over the wings. Touchdown from an estimates 25’ was on the left main gear, left of runway centerline, in a drift toward the left edge of the runway. The Board discounted copilot testimony that the left propeller touched first, since there was no physical evidence to support this view point. The actual touchdown point could not be accurately determined because there was no physical evidence left on the runway. Further, distance from the original touchdown point could not be properly assessed because of the following unknowns: Distance traveled in the initial bounce; distance traveled during the subsequent short roll; distance to clear the vehicle, and amount of power applied to clear the vehicle. Having first touched down at an estimated 300-400’ from threshold, leaping over the vehicle where it crossed the runway at 832’, the aircraft was estimated by the board to have make final touchdown at 950’ -975’ down the runway. In analyzing this portion of the flight, the Board dwelt on other actions that the pilot might have taken once faced with the vehicular traffic in front of his aircraft. The conclusion was firm that the vehicle and passengers would have been hit during a normal landing roll, likewise it was most probably that had normal go around procedures been initiated, the resultant collision would have been inevitable but with a high likelihood of material damage also to the aircraft making a successful go around questionable. The Board also analyzed the probability of a successful go around after the vehicle had been cleared before the pilot received stall warnings. This procedure, too, would have been of questionable outcome in the Board’s view, for with dissipated airspeed, a nose high attitude, wing flaps in the full down position, elevator trim still set for landing, neither time, altitude, nor remaining runway would have insured a safe recovery. This would have comprised a maneuver for which the pilot was not trained. Considering the aircraft’s position and configuration, there was a strong possibility of an aggravated power on stall the result of which could have been catastrophic. The Board therefore concluded that the primary cause of the accident was the fact that the motorcycle crossed the runway immediately in front of the landing aircraft. For although the motorcycle was not involved in the accident it forced the pilot to place the aircraft in a stall, from which a safe recovery was most unlikely. The Board next addressed the landing roll of the aircraft following it’s touchdown left of the runway centerline. According to statements, testimony, and physical evidence the aircraft was heading for the left edge of the runway and the wheels were rolling. Both pilots testify to the use of full right rudder at this time and light right wheel braking is firs evidenced at the 1050’ point. Although the aircraft was starting to straighten out it was still rapidly approaching the left side of the runway. At the 1025’ point, heavy right braking was indicated followed at 1260’ by heavy left braking on foot from the left edge of the runway. The aircraft paralleled the centerline at this point, and at 1312’ the right propeller struck the runway followed by the left propeller at 1322’. Propeller marks were intermittent, the right continuing to 1405’ and the left to 1450’. Although technical figures were not available to accurately assess braking coefficient, it was determined that the wheels, during heavy braking, were rolling with an estimated 30-50% rolling skid (15-20% rolling skid is optimum for the C-47). Both tires showed evidence of scaring from the braking effort, but neither revealed any flat spots which would have signified full skid. Propeller contact was attributed to the cumulative effect of heavy breaking on both wheels combined with the position of the elevator control, which according to testimony, was still in the neutral position. The pilot, in his post accident statement, indicated that when he was faced with imminent departure from the runway, and that when the effect of full rudder proved nil, he would risk the possibility of propeller contact by applying hard braking in an attempt to keep from leaving the runway and or stop the aircraft as soon as possible. It was only after propeller contact that the aircraft control column was pulled aft of neutral and the tail of the aircraft place on the runway. At no time was differential power use to effect a heading change. From marks left on the runway the aircraft started to the right at 1450’, and at 1575 veered more sharply still to the right. Heavy left braking was indicated at 1600’. At 1750’ the runway centerline was crossed, the aircraft straightened to parallel the centerline and both propellers separated, the left striking the runway a measured 1875’ where a mark was found. The left propeller bounced under the aircraft striking and damaging the right auxiliary fuel tank stress panel, the fuselage just aft of the wing root and the right horizontal stabilizer. Braking was continued and the aircraft came to a stop at a point approximately 2100’ from the threshold. The exact stopping point and the point of contact of the right propeller are undetermined because the aircraft and both propellers were pushed or carried from the runway prior to the investigation starting, to allow the landing of other aircraft. Crew evacuation from the aircraft was without incident or injury. The engines were shutdown by the pilots cutting off the mixtures and the fuel boost pumps were turned off. The aircraft batter switch was left in the ON position; however, the Board did not deem this significant to the accident or the resultant damage. The Board analyzed the pilot’s action after the final touchdown and drew the conclusion that these actions were a contributing cause in the accident. Several possibilities were addressed and each studied. The first of the options available to the pilot after the failure of the rudder to effect dontrol, was the use of differential power, rather than the brakes. Technical orders procedures for maintaining directional control is the application of rudder, differential power and brakes in that sequence. Differential power was not used. Secondly, the Board noted that the elevator control had not been brought to the aft position until after the propellers had made runway contact. The Board was of the opinion that there would have been no propeller contact had the elevator control been pulled aft prior to or even concurrent with heavy braking. Aerodynamic forces in this aircraft are such that the elevator is effective in changing the aircraft’s pitch attitude even at low airspeeds and is highly effective in counteracting nose pitch down when braking is applied. The Board therefore assessed the pilots use of heavy braking action with the control column in the neutral position as a contributing factor in this accident. Impact: The aircraft never completely left the runway. The left main gear went off the runway at 1275 feet from the approach end of the runway. Propeller/ground contact started at 1312 feet down the runway, shortly after extremely heavy braking commenced. The left main tire continued off the runway (Maximum) two feet off) until 1350-1475 feet down. At that time the aircraft started back toward the center of the runway with the right main tire crossing the centerline 1750’ from the approach end. At 1875 feet the left propeller separated causing the sheet metal damage. The aircraft was straightened our and stopped approximately 2100 feet down the runway, four feet right of the centerline. Crash Response: TAN PHAT is an uncontrolled airfield with no crash response capability. Adequate assistance was rendered by ARVN and US Army Advisors to remove the aircraft and propellers from the runway. Medical assistance was not necessary. Maintenance-Materials: There were no maintenance or material factors involved in this mishap. All systems, with the exception of the engines, were in good working order following the mishap. The aircrew had no difficulty with the engines and they were operating properly up to when the propellers made contact with the ground. Publications and Directives: Applicable flight publications were found to be current, on board the aircraft, and available for crew use. Normal operation in the 360th TEWS does not include landings at uncontrolled airfields. However, as proven by this mishap, landing at an uncontrolled airfield becomes necessary at times. The squadron does not have any written instructions or procedured for pilot to use when it becomes necessary to land at an uncontrolled airfield. Although we cannot say for sure, this mishap may have been avoided if the pilot had made a more thorough attempt to warn personnel of the ground that he was going to land. Supervision: The Board determined that with the possible exception of the lack of a written procedure for landing at uncontrolled airfields, supervision was adequate. The fact that a relatively low experienced crew was launched immediately after receiving the weather advisory was examined. Although Lt. Moran was relatively inexperienced, he was a fully qualified Aircraft Commander as was his co-pilot. Supervisory personnel did visit the weather station to personally check the weather. They also received a PIREP from the aircraft that was returning from Lt. Moran’s mission area indicating that weather was not a problem. There was no reason to believe the mission could not be safely accomplished. Pilot Qualifications: The pilot received his stan/eval flight check on 21 May 72 and was certified as a fully qualified Aircraft Commander. Comment by all instructor pilots throughout Lt. Moran’s upgrade training indicating excellent aircraft control and outstanding knowledge of procedures. Lt. Moran had a total of 832.2 hours with 467.8 hours in the C-47 aircraft. Although relatively inexperienced Lt. Moran was considered fully qualified to fly this mission. Weather: Weather was a factor in this mishap only in that it influenced the pilot to land at TAN PHAT. Thunderstorms had been forecast for the area. Lt. Moran was aware of the forecast and was well aware of the thunderstorms. The airfield selected for landing was in fact VFR until after the landing and mishap took place. The winds and light rain experienced had no bearing on the accident. Air Base: TAN PHAT runway is 2800 feet elevation, 4200 feet long and 100 feet wide, adequate for C-47 operation. The physical characteristics of the airfield had nothing to do with this mishap. As previously noted, the free access of vehicles to the runway was the primary cause of this mishap. This fact is adequately noted in the TAD. Life Support: No injuries resulted fro this accident. The location, an improved airfield, precluded the need for life support equipment. FINDINGS: Primary Cause: Other personnel, in that an unknown person drove a motorcycle across the runway directly in front of the landing aircraft. Contributing Cause: Operator Factor in that the pilot applied control forces and brakes in such a manner as to cause the propellers to contact the runway. Possible Contributing Cause: Operator factor in that the pilot did not positively identify the airfield where he was landing. RECOMMENDATIONS: Primary Cause. That all pilots be re-briefed on the possibility of vehicles and/or pedestrians crossing the runways at any uncontrolled airfield. (Action: 377ABW/DO). That procedures for landings at uncontrolled airfields be established, to include as a minimum, methods to insure adequate warning of the impending landings to all personnel on the ground in the immediate vicinity of the airfield. (Action: 377ABW/DO). Contributing Cause: That all C-47 pilots be made aware of the possibility that the propellers may contact the ground during heavy brake application when the control column is not full aft. Possible Contributing Cause: That all pilots be briefed concerning the circumstances surrounding this accident, with emphasis on the importance of positively identifying the landing airfield. (Action: 377ABW/DO). Action Taken: Contributing Cause: An Air Force Form 847 has been submitted recommending a caution note be added to T.O. 1C57-1 {{Should that not be T.O. 1C47-1}} advising pilots of the possibility of propeller/ground contact during heavy braking.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|